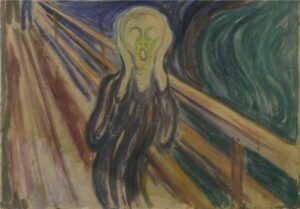

There is a woman in a spiritual community I participate in that seems to be in a constant state of suffering. Her large eyes openly plead for some kind of rescue. When any of us interact with her, we usually hear about her illnesses, her depression, her financial woes, and how it all began when a relationship ended over ten years ago.

Any kindhearted person would feel sympathy for such a person, and I initially spent a lot of time talking to her and offering support. However, over time and with repeated exposure, I began to feel the urge to avoid her; I found her constant clinging and complaining to be energetically draining. And I’ve noticed that others in the community have begun to pull away as well.

Ironically, this particular community is guided by the idea that each person creates a life that is molded by what they focus on, talk about, and believe. So perhaps this woman is our teacher. She is a living example of what happens when thoughts and words are constantly negative, hopeless, and self-limiting.

But I’ve also asked myself, is my increasingly negative reaction to this woman unfair and unloving? Aren’t there people in the world who endure suffering beyond their control? What about people living in war-torn countries? Victims of the Holocaust and other ethnic purges and massacres? What about the sick and dying? And what about those gray areas? Are addicts (including people suffering from the newer varieties like food, sex, and shopping) suffering from something completely beyond their control? What about the mentally ill?

Recently, I’ve been rereading the second half of Victor Frankl’s amazing and transformative book, Man’s Search for Meaning. The first half of the book recounts his experience of survival in the concentration camps of World War II. Rather than focusing on the horror, however, he describes how those few who survived tended to be individuals who found some form of meaning to sustain them — perhaps hope for reunion with a loved one, or in Frankl’s case, a desire to rewrite the manuscript he had just completed before his whole life was torn from him. As Frankl points out, having a purpose that provides meaning can help an individual to survive even the most dire illness or hardship. Will power may truly be the ultimate power.

The second half of Frankl’s book outlines a branch of psychotherapy that he created after the war — logotherapy. Instead of seeking pleasure (Freud’s take on the goal of humanity), Frankl believed that what makes us truly human is our perpetual quest for meaning. He says that meaning can be found in one of three ways: 1) through achievement or some form of action in the outer world, such as work, family, or service; 2) by learning and experiencing things; and 3) through suffering.

But, as Frankl emphasizes, not all suffering is created equal. To provide meaning, it has to be unavoidable suffering. If one’s suffering can be alleviated, then not doing so is merely a form of masochism.

Hence the gray areas. Is an addict actively and earnestly trying to do something in order to address their addiction, or are they merely wallowing in it or using it as an excuse? Those who do nothing to address their addiction tend to not win much sympathy from others.

The same can go for those suffering from mental illness. This is an area in which I have some personal experience. My brother has suffered from schizophrenia and bipolar disorder almost his entire life, and he is probably on the autism spectrum too. Yes, he has suffered tremendously. What could have been a productive and successful life was destroyed by an illness that was not his fault. But the truth is, my brother also tends to use his problems as an excuse — often when he wants something or doesn’t want to do something.

Happily, there have been better times too. When my brother has truly made an effort, he has tended to do much better. These are the times when his lifelong suffering has found some kind of meaning. They are the times when my brother slowly grew in wisdom and dignity through his suffering. And the same thing happens when an addict seeks help and truly makes an effort in some meaningful way.

As Frankl points out in his book, even in the concentration camps, where inmates were stripped of every vestige of their humanity and lived in constant filth and hunger, often on the verge of death, there were those who somehow found meaning and dignity in their situation. These people underwent a personal transformation that sometimes enabled them to survive. But even if they didn’t survive, at least they died with greater dignity and served as an inspiration to others around them.

So how do you suffer? Do you complain endlessly to those around you? Do you make an earnest effort to alleviate your suffering? Do you try to find some meaning in your situation and try to at least learn and grow from it? Are you able to find a way to push beyond your suffering, maybe even create a vision of a better life (perhaps even use active consciousness to help shift your situation)? You may discover that how you handle your suffering can make all the difference — not only in your relationships with others, but also in the nature of the life you begin to experience without and within.

“To be sure, a human being is a finite thing, and his freedom is restricted. It is not freedom from conditions, but it is freedom to take a stand toward conditions… Man is not fully conditioned and determined but rather determines himself whether he gives in to conditions or stands up to them. In other words, man is ultimately self-determining. Man does not simply exist but always decides what his existence will be, what he will become in the next moment.” — Victor Frankl